Building a Go Community in Edmonton: Teacher Li’s Story

At the beginning of 2024, a small message posted two months earlier quietly appeared on the Chinese social media page of the Canadian Go Association. The author was Teacher Li, a retired Go educator from Qingdao. Holding an Amateur 4-dan certificate and a national Level-2 referee license, he had devoted the past four years of his retirement to teaching Go.

What he didn’t know was that this message would soon lead him to a new chapter—one that begins in Edmonton, thousands of kilometers away from home.

A Teacher Without a Classroom… For a While

Settled in the southwest corner outside Edmonton’s ring road, Teacher Li longed to continue his Go-teaching journey. Yet for months, he couldn’t find any active Go organizations in the city.

When we came across his message, we immediately reached out. Within days, he was connected with Edmonton’s small but passionate Go community. And from there, everything began to unfold naturally—like the quiet opening moves of a well-played game.

A Class Passed On, A Mission Continued

By coincidence, Teacher Cai from the Western Canada Cultural Centre was preparing to relocate to Toronto. His newly formed Go class needed a successor. That’s when Teacher Li stepped in.

The class had opened just a few months earlier, in September, with ten enthusiastic students. The teaching resources were modest—certainly not what one might find in China—but Teacher Li saw it differently. In countries where Go is far less widespread than in China, Korea, or Japan, having any space for learning and exchange is already a gift. He poured his passion into this room, turning it into a home for beginners and young players alike.

Thank you, Teacher Li, for bringing your love for Go to Edmonton.

Summer, Dominik, and the Coolest Grandpa Ever

Teaching Go wasn’t the only pleasant surprise in his new life abroad. At home, Teacher Li began teaching his 7-year-old granddaughter, Summer, how to play. One day, Summer’s classmate Dominik showed interest in the strange black-and-white stones he saw.

And so, with Summer acting as a tiny translator, Dominik became Teacher Li’s newest student.

A Go-playing grandpa who teaches your best friend too—does it get any cooler than that?

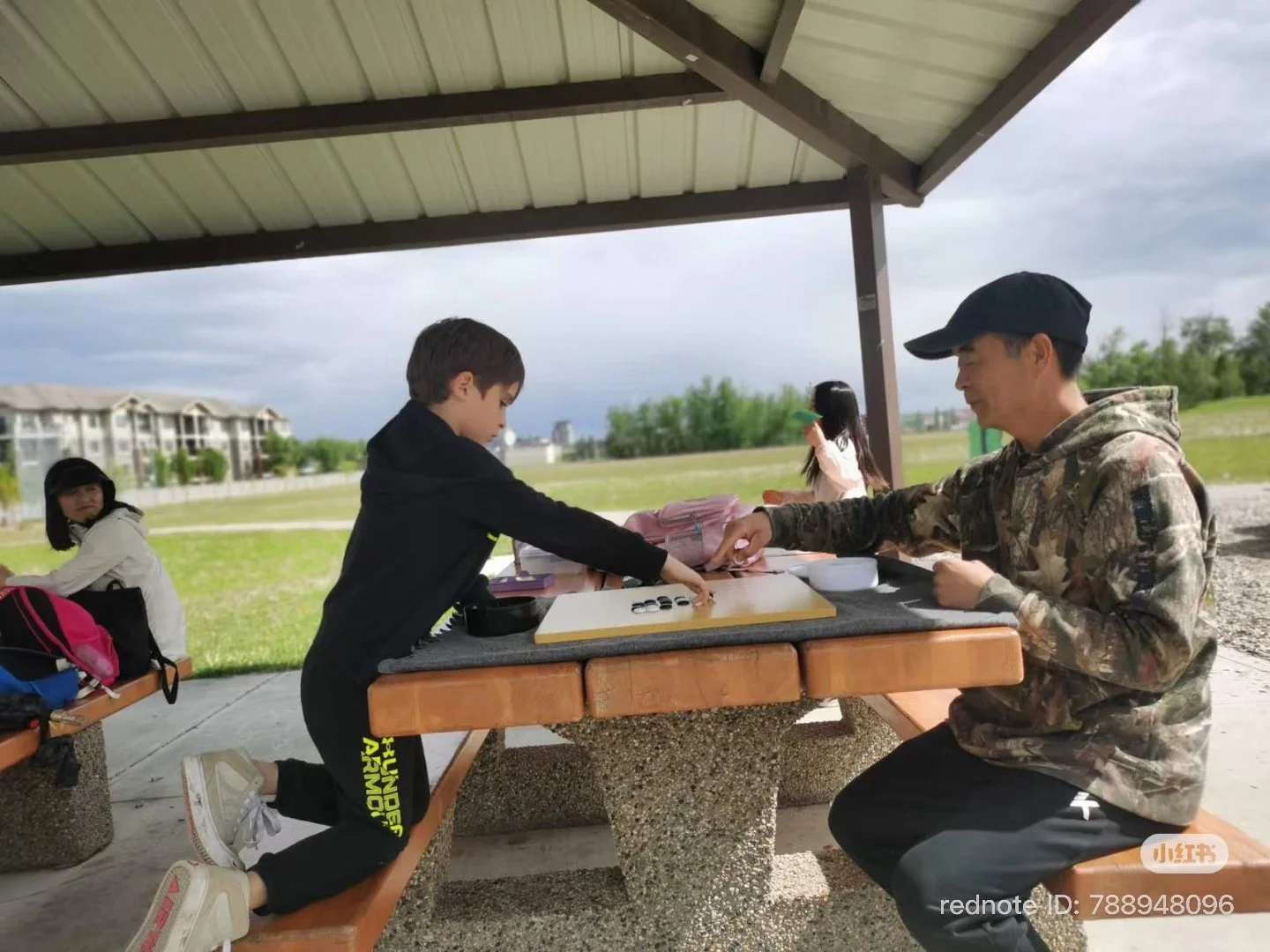

Go in the Park: Learning Under the Open Sky

When the weather turned warm, Teacher Li took Go outside.

He drove 5.7 kilometers to the park at Esther Starkman School and taught an open Go lesson for children—right there on the grass, with sunlight filtering through the leaves.

Edmonton might not have many Go classrooms, but Teacher Li proved that anywhere—a park, a playground, even a picnic table—can become a Go dojo.

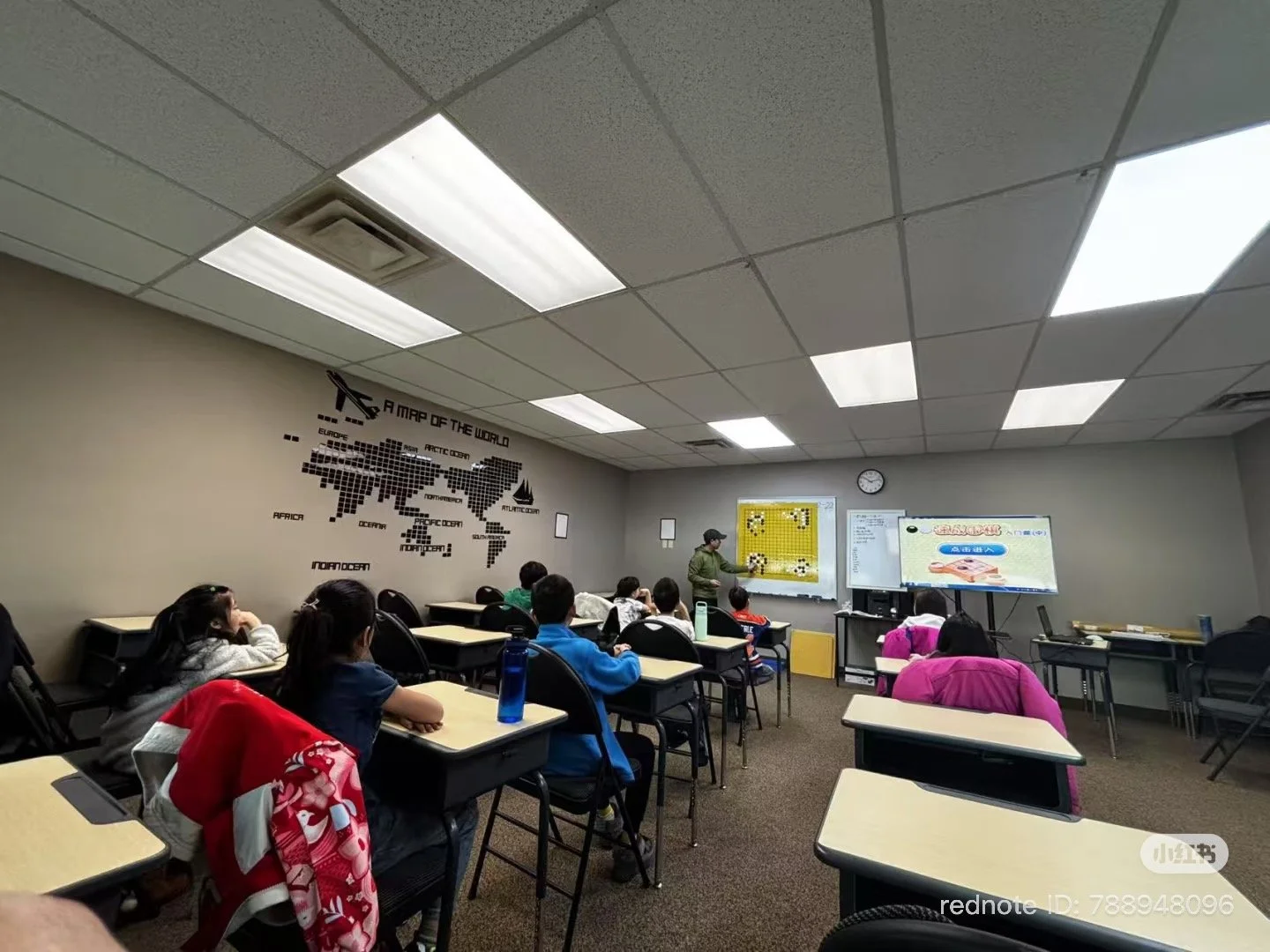

A New Classroom at Master Academy

Teacher Li officially opened his Sunday Go class at Master Academy in March 2025.

But what makes this classroom even more special is what the students play on:

A Go board handmade by Teacher Li himself.

Since teaching boards were not available locally, he rolled up his sleeves and crafted one. Passion, after all, is the best teaching tool.

Beyond One Classroom: Camps, Kindergartens, and Community

Teacher Li’s energy seems limitless. Besides teaching at the Western Canada Art Center and his own home studio, he also:

Hosts public Go lessons in parks

Visits local kindergartens to introduce Go

Collaborates with Teacher Xue’s Chinese School to run weekly Go summer camps

Slowly but steadily, Go is taking root in Edmonton—one child, one classroom, one park at a time.

Edmonton’s First Go Promotion Tournament

On May 11, 2025 another milestone was reached:

The first Edmonton Go Rank Promotion Tournament, successfully organized by Teacher Li.

For many students, this was their first taste of official Go competition—nervous faces, proud smiles, and the joy of receiving their first certificates. The local Go community has never felt more alive.

Where the Story Goes Next…

As we share these moments, Teacher Li is temporarily back in China. He is now volunteering as a Go instructor at a primary school in the Daliang Mountains—another story of passion, culture, and the power of Go.

We will share more about his experience there soon.

Until then, Edmonton continues to feel the imprint of his dedication. And beyond the board, the stories keep growing.

The Best Move on the Board: An Interview with Michael Redmond

It all begins with an idea.

The original article comes from the Go Magic.

When Michael Redmond started a YouTube channel in 2020, I was overjoyed at the opportunity to watch extensive, free lessons from an American 9 dan professional Go player. There are other channels teaching Go in English that are fantastic, but here was a man more accomplished than any player in the West, happy to share half a century’s knowledge with anyone who had the time to listen. This channel was a gold-mine for amateur American players who were serious about improving and who were willing to get into the fine positional details of the game.

If you aren’t a Go player or weren’t tuned in to the historic AlphaGo vs. Lee Sedol matches where Michael was commentating, you might not know why he’s such a big deal. The Western World has been catching up in both love and cultural capacity for the game–and for someone born in America to compete professionally at all is rather significant. Not only did he travel across the world to do that, by the age of 37 he achieved 9 dan, the highest rank that a professional can be given. Not only is he a shining example of competitive success to Western players, he is a generous educator who stays engaged with the global community of Go students and enthusiasts.

How did Michael Redmond get so good at an Asian game, being born in the United States in a pre-internet world? When did he get his start? Who taught him? What truly sets him apart? In my search for answers, I asked Michael for an interview. He was kind enough to offer his time, and well, here’s what we talked about:

(Answers slightly edited for readability)

Table of Contents

The Opening moves of Michael Redmond’s Go Career

You got your start a bit later than the typical professional….

“Right, very much so. I learned the game at the age of 10 or 11; my father taught me on a 19×19 board. They didn’t have the idea of learning on small boards at the time. So that would be very difficult. I would play him and the whole board would be dead. After a while, I got the knack. I enjoyed the idea of playing sets of games where you could change the handicap. I’m not exactly sure what the system was, something to do with three games so maybe we played three games and if I won two out of the three, it would promote. So in that case, the handicap system seemed to work really well. It was something I could handle whereas when I was playing chess against my brother or my father, any change in the handicap would have been pretty drastic.”

So you were, even with nine stones, losing a lot on the big board.

“More than nine stones, but yeah.”

I think to some kids that would be daunting or kind of discouraging?

“Yeah, I was very upset when I lost at first because it was so complete, devastating–but for some reason I just couldn’t give up on the game. I had to try again. Time after time, until I started winning. I don’t really have any logical reason for that. It just grasped me.”

I can relate to that sentiment. I’m curious–in the time before that, you said you played some chess, but what other kinds of things did you take interest in before Go?

I liked all sorts of games, I liked to read books. You might say I liked to play with my mind, entertain myself that way. And there was something about the element of chance in games like card games and games like that… it bothered me. And so I tended to like chess better than that and card games that involved more skill.

You liked Go enough and obviously showed enough promise, that you ended up going and studying in Tokyo, correct?

“My father had a number of Go books, and some of them were in English. The one set of books that really changed me most was a set of tsumego problems, life and death problems, that was in Japanese. The whole book was in Japanese and I couldn’t read it but of course it was just the diagrams and I learned to recognize the character for ‘black’ and ‘white’ and for the correct answer. There’s a relatively simple character that means ‘correct’ and when I think of it now, the character for ‘incorrect’ is relatively simple too, but it was slightly more complicated. So I just figured that everything that wasn’t the right answer was probably wrong… I worked through those books and I think that was what brought me up to what was then a shodan level. And I started going to Los Angeles for Go tournaments.

At the time there was a Japanese Go club in Los Angeles called the Naku Kim. I started going to that tournament when I was a 4 kyu I think. They had a tournament every three months. So every time I went they would say ‘you’re upgraded two ranks.’ They would just promote me without even asking. And it was a handicap tournament, so the rank was important. But I did fairly well in that tournament, so I got some trophies there. That’s actually where I got the trophy that was used for the The Redmond Cup, which is a tournament that I created for children in America to play Go.”

“So the people in Los Angeles, they told me that I was a genius. Because when I think of it, it was obvious because I was the only child. There were probably some fairly young people in their twenties or thirties maybe but most of them were old so they said ‘you’re a prodigy, you have to go to Japan.’ And I believed that. There was this guy called Richard Dolen, who actually knew my parents so they were close enough, and he offered to take me. He was going to Japan maybe once every two years, something like that, he said he went there fairly often just to visit friends and things. He was fairly close to the Go community. So he introduced me to Go in Japan and he took me there. First time I went, I was thirteen years old, and I just went for a summer vacation. By the time I came back I decided I wanted to be a professional player.”

That was one of my questions, about that moment of knowing this is what you wanted. And so that was on that trip?

“I have a memory of the first day we arrived. The Go Association in Tokyo had a floor that was a hotel floor, so we could actually stay there, and Richard Dolen booked a room in that hotel on the first day. So we arrived in Japan and went straight to the Go Association, and when we looked at the playing room there was someone playing a simul game. He was doing something like a ten on one. I have this memory of him just walking along a long table of people, sort of curved, that’s my memory of it. And I don’t know who he was. I didn’t recognize the name, of course. I knew almost no Japanese at the time. So the one thing that I remember is that he was celebrating his promotion to 9 dan. There are some people that it could be, but they don’t remember either. So I don’t know exactly who it was. I thought I was a shodan at the time and he gave me 8 stones, and I lost by one point. I had the feeling that he had some control over that, and just made the game so much more of a challenge for me and so much more exciting to have actually interacted with a player at such a high level. If you choose one thing, that was what made me decide I wanted to continue in this competitive environment.

“Because, at the time there was no internet of course. And, there were relatively few strong players in America. I was on the west coast, and so I played some in Los Angeles. There was a point where I played the stronger players in San Francisco, and I was close enough to them that I could imagine that I would soon be the strongest player in America. So I think when I played the player in San Francisco, it was actually when I had come back from Japan the first time and I was something like, I was calling myself a 4 dan and he was still a bit stronger than me, but I could imagine that I was going to surpass him. And so I was thinking ‘and then what will I do?’ I wanted to go to Japan where I knew there would be stronger players.”

Michael plays Yoda Norimoto 9d. Photo credit: British Go Association

So you saw your capability, you saw your love for the game, and you played somebody who seemed in the simul not just beat you, but beat you in this sort of conversational way. That’s really neat.

“Of course there were some other experiences too, with some other pros, but the first one is the one that made the biggest difference. Also, I think there’s the fact that I had not really come to the point where my progress was slowing down. You know how children tend to be so fast when they promote, so I was still at the point where it seemed relatively easy to me moving up in the ranks, and I definitely did not have the idea that it would get slower. I was thinking maybe in a year or so I’d be the strongest player in America.”

What a feeling. I imagine that would be very exciting

“Well, it was exciting, but also disappointing that I wouldn’t be challenged after that. I had that feeling. So that was one of the reasons that I wanted to come to Japan. Or it would be Asia nowadays. At the time, no one knew about the Chinese or Korean Go communities. They did exist. But they definitely were not internationally recognized because the countries were still recovering from WWII, I think is the main reason. So they weren’t really as active as Japan. All I knew about was Japan. I didn’t even know that Korea and China played Go.”

Go in the West vs Go in the East

So, back then, it seemed very quickly you realized to really grow, you needed to go to Japan. How much has that situation changed? If there was another you rising in the ranks today, is it still the case that they would need to go study in Asia in order to accomplish what you’ve accomplished?

“Ideally not. The world is connected now. So what I’m seeing is, up to the level of professional strength, players in America and Europe can improve. A serious player can use an AI or can play games on the net. If they play on the net they just have to find the right opponents. Even pros play on the net. So there’s no lack of opponents, which is the biggest problem that I had. So that can be done in the West. The problem is that, to be a top professional, you have to continue improving into your twenties and thirties, until it becomes too difficult. Well, you have to continue improving, throughout your life basically. Players like Shin Jin-seo, the world champions we have now, they’re still studying very hard just to keep ahead of the younger players who are challenging them. You have to continue like that.

“A difference I see with players in the West compared to players in the East, is that it’s not going to be rewarded. They don’t have tournaments to play in. They don’t have the same number of sponsors that Japanese players have. They probably would rather get a job that pays. I see a lot of these potential professionals who are actually very successful in whatever job they want to do. They’re going to take the job that gives them a livelihood, and so what I see is I think that it’s very difficult for someone to be completely focused on Go. Even in Europe and more so in America. It’s just that there’s not any money in it. Or the money in it is limited to a small minority of professionals who would be good at teaching or doing some other kind of business related to Go.”

Right. I think I’ve come into contact with more professional educators.

“Right. Teaching is not so productive for improving your own skill. I’d like to believe it helps in a way, but it’s not the most productive way of doing it. So again, there’s this handicap because of their environment. It’s not the environment of opponents because they can get opponents on the net or with an AI, but there’s that handicap that they’re not getting paid for studying.

“The ideal example of that is the Edo era in Japan- that’s ancient Japan when the country was closed; the government was actually subsidizing Go schools and the members of those schools could just play Go. They didn’t really have to hustle to get money at all. They just studied Go and were 100% Go players.”

Yes, that’s a very big difference from living on this side of the world.

“When I came here, there were newspapers sponsoring Go tournaments. Go was one of the best things people could do with their spare time. It was what people did. A very popular game. It meant that the newspapers were getting a lot of merit from having a Go column, which actually helped to sell the newspaper. So that’s obviously, with the net now, that’s something that’s changing but, I think still Japan does have an abundance of sponsors which is not present in America. Public interest in the game incentivizes more support. At the present it’s not possible, but maybe it just needs some more time to grow in the West.”

And you do see it growing?

“I think there’s more public interest in the West now. There’s always been some pop culture that includes Go like in novels or movies and stuff like that and I think that’s gradually growing especially on the net. And because AlphaGo, now just about everyone knows there’s a game called Go. There’s a stronger presence than at my time, when no one knew what it was about.”

Your Best Teachers are your Rivals

I’m wondering how important you think it is to have a consistent teacher or mentor? Did you consider yourself the student of a particular teacher, or was your learning pretty independent?

“I’d say my teachers were my rivals. I think that there still is a lot of value in face to face contact. Because when I was interacting with other professionals, I think there’s a lot of body language, face language that comes through even when they don’t actually say so much–during a game, or when they’re looking at my game. Japanese aren’t so outgoing in disagreeing with what you want to do, but you can read a disapproval or a questioning feeling when it’s face to face, so I did get that. My teacher Mr. Oida, at the time he was sort of in semi-retirement. And he was in the administrative part of the Go Association, so he was running the business. He said himself that he didn’t consider himself a good teacher, he didn’t have the instinct that an active pro would have because he wasn’t playing so many games.

Photo credit: British Go Association

“He did have a friend come over, Miyazawa Goro, who was, when he started teaching us, a 4 dan. He’s a 9 dan now. He was moving up in the ranks, and he influenced me the most, maybe. He was a very aggressive fighting player, probably the most at the time. He was probably the wildest fighter in Japan. He was the person who challenged me to put some more fighting power into my game. He would get upset when I was playing josekis just because they’re in the book. He’s also a person who made me go through all of the classical tsumego collections. All of the life and death problems, all the difficult ones that are so hard for pros even, he made me go through those a number of times. I think he told me I had to go through them about three times if I wanted to become a pro.”

The Four Corners of Michael Redmond’s Career

You have a YouTube channel and you offer lessons, and also commentate and still play. Would you say you enjoy these things equally, but differently?

“Yes, definitely differently.”

Competition:

“Playing as a pro is very challenging and your opponent is also a professional player. He’s trying to win also. And it’s very painful because people make mistakes and you realize you’ve made a mistake and the whole process is actually a pretty painful thing. But it’s also very pleasurable in a different way. It’s a very intense experience just to play one game. In a way it’s very satisfying although you can be disappointed about some mistakes. It’s a very satisfying experience, fighting out such a difficult game.

Commentary:

“Commentating on live professional games is also challenging. I don’t do it so much now because the TV networks have reduced the amount of time they use. There was a time when I would be doing it quite a great deal, actually. Twice a month I would commentate on a live professional game. That was really challenging because well, first of all they’re the top players in the world, so the level of the game is challenging also. The fact that I had to talk while I was thinking about the game itself was very challenging and it was balancing that was exciting and challenging that way. And there was some interaction with the people who came to watch if it was with an audience. That was fun too. Sometimes they would ask questions, and of course there was a coordinator too who’d be another professional player or maybe just a strong amateur who would be asking questions also, I would find that sometimes interesting.

Youtube:

“When I was young and when YouTube came to be, to be frank I didn’t think much of it, I thought it was some trashy thing, and I never paid attention to it until AlphaGo. Then Google contracted me to do the commentary and they posted it on their page. Basically a YouTube video, and the first day was like a million logins. Over a million. This huge number and I just knew that they couldn’t all be Go players. It was because AlphaGo was in the main media.

That’s when it hit me how powerful YouTube could be, and it made me want to start to make YouTube videos. I didn’t actually immediately do that. It was the Covid virus that started me on YouTube because things slowed down drastically. So I had a lot of time on my hands. I thought it was an opportunity to learn how to make videos. It’s not as personal you might say as the tournament games. My ability to move forward to the next game depends on my winning a game, so it’s very important every game that I play. I have maybe a slightly more casual interest in improving my ability to do the videos, but people are nice and saying I do a good job so it makes me happy.”

I would say you are. I do want to ask about teaching lessons too.

Teaching:

“I had this problem that I played so few games when I was a child, only with people in Santa Barbara who would gather together once a week or something like that. And then I would play some games with my father. My teacher said I was short on the number of games I had played, and so he went against the Japanese historical traditional method, which says that you’re not supposed to play with players weaker than yourself. He made me play a lot of handicap games. When I was a kid I was just enjoying destroying people like that, but I gradually started to see patterns, you might say, in the mistakes they made. People have these habits that they form which they think are working, but when they’re a weak Go player, sometimes the habit is just wrong and it’s exploited by stronger players every time. And so I think I began to develop an eye for finding those mistakes and I transformed from destroying people to trying to help them solve those problems.

“I was doing a series of lectures for the NHK. The NHK Cup is broadcast once a week on Sundays and they have this twenty minute lesson that comes before the tournament. The lesson is for relatively weak players, and I did a set of lessons on how to attack using handicap games as the context because black has an advantage. It’s very efficient to attack in handicap games, because say you have 4 stones, you have a 4 to 1 handicap. It’s interesting to show how the handicap gets smaller and smaller as you progress—if you play defensively, it’s gonna be a 104 to 101. You’re gonna lose the fight if you start it then. When I made this series of lectures, I sort of changed status into becoming someone who was trying to help people overcome these bad habits, and it changed the way I saw my teaching. After that, I think I became slightly better at telling people about how to improve their games. That’s the main theme of what I do now. When I actually play teaching games, I don’t make it easy for the opponent. I’m not capable of playing nice moves that will help them. I try to play the best move in any case, which is not the way most Japanese teaching-pros teach. The game itself is tough, but it gives me the opportunity to find the weaknesses of the player and tell them what they should do next to improve their game. I think I’ve become fairly good at seeing that, even in one lesson.

“In my twenties, it was important for me to focus on winning and improving my own game and it was natural that I wasn’t so interested in teaching at the time. But now, I’m in my 60’s, so it’s much more difficult to be successful in the Go tournaments. And I think it’s healthy and natural that I’m making a shift towards teaching.”

Moves Worth Remembering

What’s one of your most memorable recent games that you’ve played?

“My recent games not so much. I really remember the games that I played in the world championships. So there’s a period when I was usually representing America. That was 20, 30 years ago. It started when I was about 5 dan and the Japanese company, Fujitsu, sponsored a world championship. That was one of the first. I think I got into two or three Ing Cups and a number of international tournaments. I remember a game I played against Nei Weiping, who was the strongest Chinese player at the time. He was called the “Invincible Goal-keeper.” There was this team tournament between China and Japan at a time when people thought Japan was the strongest country in the world still, about 40 years ago and for a number of these tournaments he was the final player for China. It was a team tournament where you would knock out one player at a time. He would be the final player for China. He would knock out sometimes 5 or 6 Japanese players. So he was the goal-keeper for China. I played against him once. I remember we got into this joseki where he played an unusual move and it still sticks in my head.

“I also remember games I played against Cho Chikun. These experiences with top pros at the time are very vivid. Cho Chikun especially because he’s always been an interesting person. He was much more severe when he was young. But I remember very vividly the first game I played against him. I had the white stones, and that was actually in the Fujitsu Cup, and he completely destroyed me.

When we were reviewing the game together, it was like he already didn’t like my move number 2. It was just a normal corner point, but there was no point where he thought I had a chance in the game, so it was quite an experience. But I played a lot of games against Cho Chikun actually, beat him twice maybe after that. All of those games were very special experiences. He was one of the players I respect the most.”

I’m curious if there’s a specific thing about him that gained that respect from you?

“He would not allow excuses to anyone, or to himself, to play the easy move in any position. He would be very strict not only with other players but with himself also about trying to find the best move in any position. He was generally a fighting player but he played a lot of surprising moves. He was one of the first players who became very good at making life in the opponent’s sphere of influence. It’s more true of younger players nowadays, but he would get into these fights that looked hopeless and he would find ways out of them. So he was a very exciting player to watch. He would get very emotional about the game and I think it’s a good way.”

With this, we wrapped up our interview, but I thought it was a good note to end on, a final point to consider: the way you become one of the best in the world–at anything–is to keep yourself and the people around you to the highest standard. There is no doubt Michael Redmond shared this mindset with Cho Chikun–never just do the easy thing. Find the best move on the board, even if it takes you to the other side of the world.

How Go & Tea Is Bringing Go to Camrose Schools and the Community

It all begins with an idea.

In the heart of downtown Camrose, Alberta, Canada, tucked above the shops on Main Street, Go & Tea has quietly become a gathering place where tea culture meets the ancient strategy of Go. Since opening in January 2024, the tea room has welcomed newcomers, lifelong tea lovers, and Go enthusiasts into its warm, community-centered space.

Behind it all is Sarah Yu, an amateur 6-dan Go player whose connection to the game stretches back to her childhood in China. Sarah began learning Go at the age of six under the guidance of professional player Ruan Yunsheng (7p). After immigrating to Canada at fifteen, she represented Canada and North America in international events, winning a bronze medal in the Women’s Individual at the 2012 World Mind Sports Games in France and finishing 5th at the 2017 EMSA women’s division.

Today, instead of competing, Sarah devotes her energy to teaching. For her, the joy of Go lives in watching beginners discover the game’s elegance and depth.

A Space Built for Connection

Go & Tea offers more than thoughtfully brewed teas and quiet corners. It has become a welcoming hub where people of all ages can experience Go in an inviting, low-pressure environment. Parents sip tea while children explore the play corner; students drop by after school; and strangers become friends over a shared interest in this centuries-old game.

For Sarah, the tea room is not just a business—it is a bridge between cultures and generations.

A Meaningful Donation to Camrose Schools

On August 22, 2024, Go & Tea donated 20 Go sets, supplied by the Canadian Go Association (CGA), to the Battle River School Division (BRSD). Assistant Superintendent Stephen Hoyland visited the tea room to accept the donation and enjoyed a demonstration game with Sarah.

BRSD later released a media statement celebrating the contribution, noting that Go supports learning in numeracy, decision-making, cultural awareness, and relationship-building. Although the initial article did not mention the CGA, Go & Tea followed up to ensure proper credit was given for the donation of the equipment.

The introduction of Go into schools sparked genuine excitement. BRSD superintendent Rhae-Ann Holoien emphasized the many ways Go can enrich students’ learning, calling it a fun and meaningful educational tool.

A Teacher, A Summer Visit, and Growing Interest

During Summer 2025, a high school physics and chemistry teacher visited Go & Tea. He was delighted to discover that Go was making its way into his school district—and even more delighted to find a local space dedicated to the game.

He purchased his own Go set and brought it to school. With the start of the school year, he began hosting lunchtime Go sessions. Student interest grew so quickly that he returned to Go & Tea to purchase five more sets. By then, even the smaller 9×9 and 13×13 boards had completely sold out.

This spontaneous enthusiasm reflects something larger: Go resonates with students. It challenges their minds, fosters calm focus, and introduces them to a unique cultural tradition.

The Story Continues

In Camrose, a quiet but meaningful Go movement is taking shape:

A tea room offering a space for reflection and connection.

A school district welcoming a new way to learn.

Teachers and students discovering a game that sharpens the mind and soothes the spirit.

And a passionate teacher—Sarah—sharing a lifetime of experience, one game at a time.

Ben Mantle-From Hikaru no Go Inspiration to Global Go Educator

It all begins with an idea.

Ben Mantle (also known as BenKyo or BenKyo Baduk) is a Canadian 5-dan Go player, full-time Go teacher, and content creator. Since June 2021, he has dedicated himself entirely to Go education, teaching through multiple platforms and building an international Go learning community. He teaches on YouTube under the name BenKyo Baduk, streams on Twitch as BenKyoBaduk, and runs the BenKyo League, an online environment where players of all levels can learn, train, and grow. He also serves as Head Instructor at the Toronto Go Club, is the former President of the University of Toronto Go Club, and has been part of the Go tables team in the Gaming section at Anime North, helping introduce Go to new audiences through convention culture.

A Journey Sparked by a Story

Like many modern Go players, BenKyo first encountered the game through the anime Hikaru no Go in 2006. What began as curiosity became passion, leading him to study intensively, explore Go theory deeply, and eventually travel to Korea to strengthen his understanding at the source.

For years, he balanced Go with his career as a software engineer—until making a pivotal decision in 2021 to pursue Go full-time. That choice marked a turning point not only in his own life but in the experiences of the many students and players he now teaches and mentors.

Building Spaces for Go to Grow

Outside East Asia, many Go players struggle without structure, opponents, instruction, or a motivating community. To address this gap, BenKyo created the BenKyo League (BKL)—a system with tiered divisions, flexible match scheduling, guided improvement, study groups, reviews, and a welcoming sense of belonging. From beginners learning fundamentals to aspiring dan-level players refining their game, BKL offers a clear path for growth.

Students describe BenKyo as patient, analytical, encouraging, and approachable. Many have progressed from single-digit kyu to dan level through his emphasis on shape intuition, reading depth, decision-making, emotional steadiness, and purposeful reviewing. His teaching philosophy focuses on how players think, not just the moves they select.

Beyond BKL, he has built a digital classroom through his YouTube channel, where he shares live reviews, joseki explanations, tsumego guidance, AI analysis, and commentary suitable for all levels. His Twitch streams add real-time interaction, blending entertainment with instruction, helping players worldwide improve—especially those without local Go clubs.

In his GoMagic interview, he introduced two complementary approaches to tsumego study: Tsumego Exposure Training, involving quick instinct-based attempts and high-volume pattern recognition, and Deep Reading Training, involving full solution calculation supported by AI review and strong sparring partners. He emphasized reviewing wins as well as losses, valuing deep analysis over quantity, recognizing that rank barriers often stem from subtle inefficiencies, and understanding that a single move can decide a game. This reflects a modern, structured, and mentally aware approach to Go training.

Through the BenKyo League, YouTube, Twitch, his teaching roles, and outreach at conventions, BenKyo has made Go more accessible and connected. His journey shows that Go extends beyond the board—becoming a discipline, a way of thinking, and a cultural bridge built through shared curiosity and black-and-white stones.

GRATEFUL RIVAL: Keith Arnold remembers Haskell Small

It all begins with an idea.

The original article comes from the American Go Association.

Haskell “Hal” Small, the father of the US Go Congress, passed away on Saturday, June 1st, two days shy of his 77th birthday. He leaves behind his wife Betsy, his two daughters, Sarah and Rachel and a legacy of joy, competition and friendship that will never end.

Hal brought us together, he connected the entire country, converting a moyo into territory.

I met him back in 1980, at the Greater Washington Go Club, but it was only after I had finished school that I was able to attend regularly. Although that coincided with the planning of the first US Go Congress in 1985, I was not on the planning team, can take no credit and in fact, had it not been held at my undergraduate school, Western Maryland (now McDaniel) College, I probably would not have even attended.

Looking back, however, I can easily imagine Hal’s role in the creation of our national event. Many of you might picture a Congress Director hunched over a laptop like Sam Zimmerman, making endless announcements, or running around putting out fires like so many of us.

This was not Hal’s way. Working with him on the planning of the later two DC Congresses and the establishment of the National Go Center, Hal was like a tidal force - not a hurricane of activity - but a slow and steady ebb and flow, a guiding current. When he decided to do something, it somehow simply became inevitable. Everything began with an invitation to his home, good food and Go boards. Gently but inexorably, Hal guided us in what needed to be done. All who worked for him became extensions of his vision.

One wonders if this ability to put together the big picture, to orchestrate these efforts, came from his day job - a composer, pianist and teacher. I cannot do justice to the breadth and true meaning of his musical career, but I can say, when my rather limited musical knowledge had some touchstones to aid my understanding, it was transformative.

Above all, his piece for two pianos “A Game of Go” was exhilarating. I had the good fortune to experience it three times; at the third Congress in Holyoke, the fourth in Berkeley and later in DC. Hal’s biting atonal music featured one piano “playing” Shusaku’s black moves, while another “played” Ota Yuzo’s white moves, each appearing on a video screen in time with the music. The piece interpreted the mood and pace - what folks today call “temperature” - of the game perfectly.

I will also never forget hearing him perform his “Lullaby of War” in Baltimore. A series of piano accompaniments and interludes matching historical poems about war. Hal’s play and his moving readings brought home a visceral anti-war sentiment. Even more unforgettable was hearing him play, one handed after his 2021 stroke, in a small church outside of Baltimore. He embraced his temporary limitations with fascination, and played with an enthusiasm fit for Carnegie Hall.

But for me, Hal will forever be the first of my great Go rivals to leave me. We Go players are nothing without each other, and in the days before the internet, it was rivals that sent us to joseki books, spurred our improvement and propelled us to new strengths. Recently, I came across some old notes in which I tracked the ratings of four or five players, including myself - a ranking of rivals - and Hal was one of them.

We were hopeful imitations of Takemiya Masaki and Kobayshi Koichi, Hal with his moyos and me with my greedy territory. His opening was perhaps slightly better than mine, and his sense of timing in the middle game was certainly superior, while I humbly submit I was the better fighter. Although I outpaced Haskell, who achieved 4 dan, while I reached 5 dan for a couple of years, I am not sure Hal ever admitted defeat, and indeed, since many of my wins seemed “lucky”, who could blame him? And while I always enjoyed our games, Hal Small was never a tournament pairing I took lightly.

One shameful memory I feel compelled to share dates back to the height of our rivalry. Accustomed to reading better than him, I remember my arrogant thoughts when he would sometimes shut his eyes as he was reading out fights. In my hubris, it seemed ridiculous; I could outfight him with his eyes open, what chance would he have with his eyes shut? It was only later that I learned that he was dyslexic. I never had a chance to ask, but I suspect shutting his eyes was a way to bring order to the board. I cannot help but admire all the more his achievements in music and Go.

In more recent years, I think of Hal and Betsy, seemingly always together, quietly enjoying the Congresses. His pride in Betsy’s enthusiasm as a Go player was palpable, as was his pride in his daughters when they would make their frequent Congress appearances. Perhaps his favorite day of each Congress was Pair Go with Betsy and I will never forget the year they traded clothes and waited for people to notice.

In contrast to his Go player’s competitiveness, and his powerful music, this was a man who seemed quietly and truly content.

A memorial service will be planned in the future. But any memorial service should be a celebration of life and legacy. And Hal will have one every summer.